Fr. Stephen F. Somerville

In the Tridentine Mass, there is a particularly solemn invocation of the Holy Trinity. It comes at the end of the Canon of the Mass, just before the Our Father prayer. This invocation has five signs of the Cross, made by the priest with the consecrated Bread and Wine, that is, the true Body and Blood of Christ. These crosses are succeeded by a gesture of elevation or lifting up of the Victim toward Heaven.

The priest prays, meanwhile, that "all honor and glory" be given to God at this usually-called "minor elevation" of the Most Holy Victim in the Sacrifice which we call the Mass. Here are the words of the full prayer:

Through Christ, and with Him, and in Him, all honor and glory is given to Thee, O God the Father, in the unity of the of the Holy Ghost, until the end of world without end.

The element of sacrifice is clearly present in the pre-Vatican II Mass |

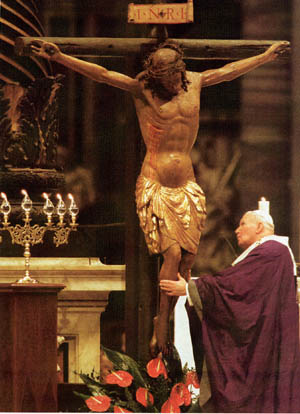

This offering is re-presented, made present and actual again, or made new, by the ordained priest every time he says Mass. It is not a fresh crucifixion of Jesus; it is not another killing or dying of Christ. It is the one and only sacrifice of the Eternal Son, now incarnate, and it is achieved on our altar by the separate consecrations of the bread and the wine. These become, by Divine Power, the true and real Body and Blood of the same Victim Christ as on Good Friday. The same Sacrifice is therefore present, is offered, and is pleasing to the Father.

Let us keep in mind that Jesus' whole life was an offering to God. He did not wait till Good Friday to please and glorify His Father. As soon as He came into the world, He uttered the words of the prophetic psalmist: "Here I am, Lord; I come to do Thy will." The Gospel records that He said: "My food is to do the will of Him who sent me." He said, "I do always the things that please Him." He said, "The Son can do nothing of His own accord, but only what He sees the Father doing (Jn 5:19)." He said, "I honor my Father." (8:49) Twice in Jesus' earthly life, at His Baptism and His Transfiguration, God the Father testified aloud to the loving obedience of Jesus by saying "This is my Beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased."

We began these reflections by declaring the sacrifice of Jesus' Body and Blood at the Minor Elevation of the Mass. It says, "Through Christ, all honor to Thee, Father, in the Unity of the Holy Ghost, forever."

But you might answer, these words do not say sacrifice very clearly. Can we be sure that the Mass really is a Sacrifice offered by Christ to the Father? The answer is, yes, we can be certain. Let us look at the Mass prayers, and see what they say.

At the very beginning, we hear three times, "I will go unto the altar of God" What is the altar? It is the sacred stone on which to offer sacrifice. When the priest climbs the altar steps, he prays "to be worthy to enter with pure mind into the Holy of holies, " which means the holy place in God's temple for offering sacrifice.

The sacrifices of the Old Covenant were prefigures of the Holy Mass |

Notice that sacrifice is being offered also for dead Christians, that is, for the faithful departed. We must remember that the Commander of the Maccabees army in the Old Testament sent money to the Jerusalem temple for sacrifices to be offered for his soldiers who had died in battle, "so that they might be loosed from their sins." So today, we Catholics often have Masses said for the departed in order to atone for their sins, and help to release them from purgatory into heaven.

Moments later, at the Mass Offertory, the priest prays to God the Sanctifier to "bless this sacrifice" and while so saying, he makes the sign of the Cross over the bread and wine, that is, precisely the sacrifice.

Then, washing his hands, the priest prays Psalm 25, a hymn of praise for the old Jerusalem temple, that is, the sacred building made for sacrifices. He says "I will go about Thy altar, Lord...I have loved the beauty of Thy house, the place of Thy glory...I have avoided evil men, whose hands are grasping sin and blood and bribes, not holy sacrifices. Be merciful unto me, my foot hath stood in the way of right, not wrong." These two prayers � the Veni Sanctificator and the Lavabo are clearly the prayers of a true priest offering a real sacrifice.

Immediately after them, the priest prays Suscipe Sancta Trinitas, with its unmistakable language of true ritual sacrifice. He says, Receive, O Holy Trinity, this oblation which we offer thee as memorial of the passion, resurrection and ascension of Christ. The priest strikingly anticipates the consecration and change of the bread and wine gifts into the very Body and Blood of Good Friday and the Easter Christ. It will not be a mere psychological, subjective calling to mind, but a concrete memorial. The flesh and blood of the Victim will really lie before our eyes.

The priest prays on, (Receive, Lord, this offering, also) to honor Holy Mary, John the Baptist, the Apostles and All Saints, that it may honor them, and save us wayfarers. Notice the Catholic care to honor both God and the Saints, and to assist ourselves, with the kindly intercession of the Saints. These are points of doctrine rejected by the Protestants: Purgatory and Intercession and Veneration regarding the Saints. The Sacrifice of the Mass declares these truths by such prayers as these.

Is it now clearer that the Catholic Mass actually affirms itself a true sacrifice of worship? Yes, it is surely clearer. But the clearest is yet to come, in the Canon Prayer of the Roman Mass. The priest begins it, still in silence as he was for the offertory prayers, and he says, "Father... accept and bless these + gifts, these + presents, these holy and + unspotted Sacrifices," and he makes three emphatic signs of the Cross over the offerings of bread and wine, as if to drive home the connection between them and the One who expired in self-sacrifice on the very Cross.

The Last Supper by Duccio di Buoninsegna |

Now comes the climactic consecration of the Mass. People tend to think that this account of what Jesus did and said at the Last Supper is copied from the four Gospels. Not so! These Gospels were written down 25 or more years after the Ascension of Jesus into heaven. But Mass had been offered by the Apostles with the early Church right from Pentecost Day and perhaps even earlier. Before His Ascension, it is entirely likely that Jesus taught His disciples how to conduct the service and sacrifice of Holy Thursday. Our Roman Canon contains details not in any of the Four Gospels. For example, the expression Mystery of Faith at the wine consecration. It clearly helps to express wonder and awe at the moment of change to the Blood of Christ. Pope Innocent III in 1202 declared we believe that the form of words in the Canon came from the Apostles who received them from Christ, and their successors from them.

We call this change transubstantiation, that is, change of substance, not of appearance. What we must specially notice here is the format of the Latin Altar Missal. The words of consecration, that is, the essential form words of the Sacrament, are picked out in very large, indented type, often with colored illumination. The priest is instructed to bow down low when uttering the words, In a self-audible whisper, with great reverence, as if he were speaking in the very Person of Christ, and this is precisely the case. It is no mere narrative of the Last Supper of Christ.

Finally, the language is clearly that of sacrifice. It says "the chalice...of the new and eternal covenant," that is, the sacrifice ratifying said covenant. It says the Blood �will be shed,� as in sacrifice. It is shed "for you and for many, unto the remission of sins," as it is in a true sacrifice intended to propitiate the Deity.

After the consecration, in Unde et memores, the priest remembers the passion of Christ and offers to God - and I quote � �a pure + victim, a holy + victim, a spotless + victim, the holy bread of + eternal life and the chalice + of everlasting salvation.� Five hand-signs of the Cross over the offerings accompany these words. The next prayer expressly compares this offering with famous sacrifices of old, namely of Abel (son of Adam), of patriarch Abraham, and of High Priest Melchisedech. Then the priest asks the Angels to carry the offerings up to the very altar of God in Heaven, just as Jesus Himself ascended to Heaven six weeks after His sacrificial immolation on Calvary. This too is clear sacrifice-language.

The purpose of sacrifice is not only to honor God, but to propitiate Him, that is, appease Him, after the offences of men's sins. In other words, Sacrifice must be pleasing to God, and must re-establish good relations, or what we call "communion" with God. Accordingly, the Sacrifice of the Mass now enters into its communion phase, and this is specially expressed by reverently partaking of the flesh of the Victim, in what we call Holy Communion. As we all know instinctively, to share food together is a sign of brotherly love. The Mass is a Sacrament of our mystical unity with Christ and one another.

I now conclude all these remarks with reference to one final, brief, but magnificent declaration of sacrifice in the Roman Mass. It is the prayer Placeat tibi just before the priest's final blessing. In brief he says, "O Holy Trinity, may my service please thee, and may my sacrifice be acceptable to thee, and be a propitiation to win thy loving mercy." It is now abundantly clear. The Roman Rite Catholic Mass is indeed a Sacrifice, truly and really, offered for the honor of God and the salvation of men. The words of the Mass say this; the gestures of the Mass reinforce it.